Neurodivergence, Trauma and Nervous System Regulation

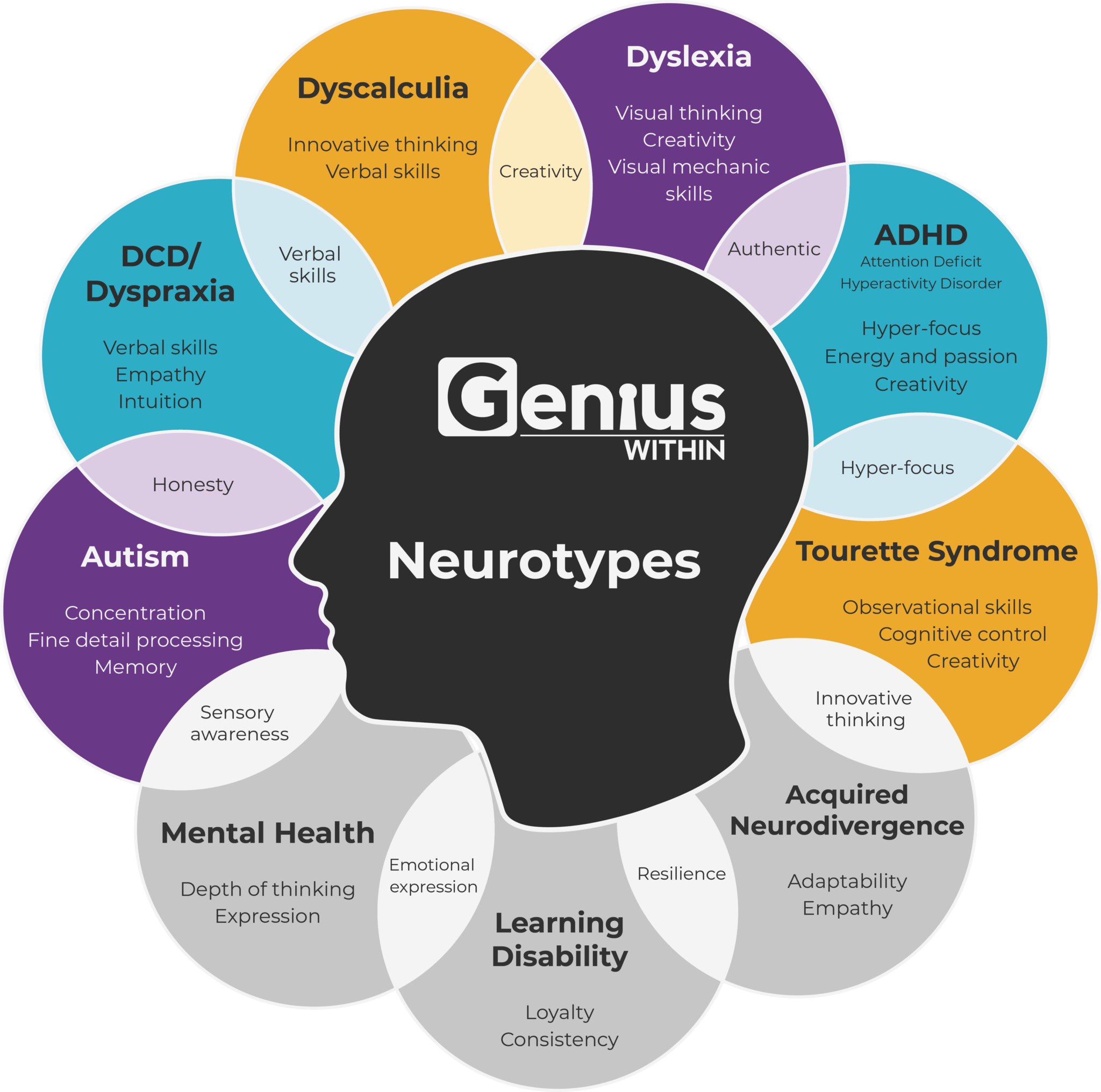

Neurodivergence is a term that describes natural differences in how human brains and nervous systems work. Autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other variations fall under this broad category. These differences are not caused by trauma. They are part of human diversity and reflect the many ways we sense, process, and respond to the world.

What Do We Mean by “Neurodivergent”?

The word neurodivergent was coined in the late 1990s by autistic sociologist Judy Singer. It arose from the neurodiversity movement, which views autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other differences as natural variations in human brains and nervous systems.

The term only makes sense in relation to neurotypical, a label used for people whose brains and behaviors align with the socially dominant idea of “normal.” This standard is based on statistical averages and cultural expectations, such as making eye contact, sitting still in school, or regulating emotions in predictable ways.

These so-called standards are cultural constructs rather than universal truths. What matters is not whether someone is “typical,” but whether their unique way of processing is respected and supported. Neurodivergence reminds us that there is no single correct brain. Diversity in nervous systems is part of the richness of being human.

Epigenetics and Expression

Emerging research indicates that genetics may play a central role in neurodivergence. Autism, ADHD, and other forms of neurodivergence run in families and involve many genes working together. However, genetics alone does not tell the whole story. Epigenetics, changes in how genes are expressed without altering DNA itself, also plays a role.

Environmental factors such as stress, trauma, nutrition, or nurturing relationships can influence whether certain genes are turned “on” or “off.” In the case of neurodivergence, epigenetics may affect how strongly certain traits are expressed. A person may inherit differences related to attention or sensory processing, and the degree of challenge or ease they experience can be shaped by early experiences.

Trauma and chronic stress do not cause autism or ADHD, but they may create epigenetic changes that affect emotional regulation and resilience. This could intensify difficulties that often accompany neurodivergence, such as anxiety or nervous system dysregulation. Families with intergenerational trauma may also pass down epigenetic patterns that increase sensitivity to stress. This means that two people with similar genetic profiles can present very differently depending on the support, safety, and care available in their early environment.

Trauma and Neurodivergence

At the same time, many neurodivergent people also live with trauma. Some of this comes from growing up in environments that did not recognize or support their needs. Constant invalidation, bullying, or pressure to mask natural behaviors can be traumatic. Developmental trauma and complex PTSD shape the nervous system by creating patterns of hypervigilance, shutdown, or chronic dysregulation. This overlap can make it difficult to distinguish what comes from neurodivergence and what comes from trauma.

Trauma does not cause neurodivergence. Autism and ADHD, for example, are not the result of adverse childhood experiences. What trauma does is interact with neurodivergence, often intensifying challenges with sensory sensitivity, regulation, and emotional safety. When we begin to recognize these distinctions, we can approach healing with more compassion and precision.

Somatic Mindfulness and Meditation

Somatic mindfulness offers one pathway of support. Instead of asking people to suppress thoughts or sit still for long periods, somatic mindfulness invites awareness of the body in the present moment. For some this may be the feeling of feet on the ground, the rhythm of rocking, or listening to ambient sound. By allowing choice and flexibility, somatic mindfulness practices honor the wide range of nervous system needs.

Meditation can also be adapted for neurodivergent practitioners. Shorter practices with clear beginnings and endings help with attention regulation. Offering a choice of anchors, such as sound, touch, or movement, respects individual preferences. Creating space for movement during meditation supports those who find stillness uncomfortable. These adaptations do not dilute the practice. They open the door so that more people can benefit.

Nervous System Regulation

Nervous system regulation practices are especially supportive. Many neurodivergent people experience frequent overwhelm or shutdown. Simple practices such as orienting to the environment, noticing what feels safe, or gently extending the exhale can help. Rhythmic activities like walking, tapping, or humming bring balance back to the system. Co-regulation through trusted relationships, pets, or connection with nature is another powerful resource.

Regulating practices build a foundation of safety and resilience that allows each person to show up more fully as themselves. When combined with mindfulness, they create a flexible approach that meets people where they are.

Stress, Sensory Bombardment, and Modern Life

The pace of modern life adds another layer of challenge. Our world rewards multitasking, speed, and constant productivity. Many neurodivergent people thrive with different rhythms, such as deep focus or more frequent rest. When the external world pushes faster than the nervous system can comfortably manage, stress builds and burnout becomes more likely.

Sensory bombardment is another factor. Daily life includes bright lights, traffic noise, crowded spaces, and the constant presence of screens. For sensitive nervous systems, this creates ongoing hypervigilance.

Social media can offer connection but also exposes people to comparison, conflict, and an endless stream of stimulation. This can fragment attention, increase anxiety, and strain already overworked regulation systems.

Chronic stress affects everyone, but neurodivergent people often carry a higher baseline load. The combined weight of sensory overwhelm, invalidation, and rapid cultural pace creates more wear and tear on the body and nervous system. This helps explain the higher rates of anxiety, depression, and burnout reported among neurodivergent populations.

Mindfulness and regulation practices can serve as buffers. Taking sensory breaks, using noise-canceling headphones, practicing orienting, and intentionally slowing down are all ways to counterbalance the stress of modern life. Building boundaries with technology and protecting time for rest create needed space for recovery. When paired with supportive relationships, pets, and time in nature, these strategies remind the nervous system that it is safe enough to relax and rest.

A Culture of Belonging

The apparent rise in neurodivergence today reflects a growing awareness, recognition, and willingness to name what has always been part of human diversity. With that recognition comes an opportunity to create spaces of belonging. The term neurodivergent is not a medical diagnosis. It acknowledges and honors natural variations in human brains and nervous systems as valid and welcome.

When we practice mindfulness and regulation in inclusive, compassionate ways, we affirm that there is no single “right” nervous system. Each brings richness and gifts, and each deserves care, respect, and tools for thriving.